Contact by Darian Leader

In one of her earliest works, painted in her teens, Rachel Howard depicts the terse, agile body of a boxer poised, ready to throw his punch. We see neither his opponent nor his background or context, only the vector of his blow, a percussion caught in oils. Now, many years later in her new paintings, there is no single human figure, no punch or blow, no evidence of any act of aggression, and yet, for the artist, these are works about violence, a violence in "all its banality” that we are spectators to - day in, day out.

Boxer 1987, Oil on canvas , 26.4 x 26.4 cm

On Violence (Spring), 2017 (Detail), Oil & acrylic on canvas, 274.3 x 274.3 cm

The new works ostensibly chart the seasons - Autumn, Winter, Spring and Summer- and one might immediately guess that the violence Howard evokes is that of the cyclical rhythms of nature, where death follows life until new life is born. When children ask about death, parents habitually use exactly this cycle to explain mortality, as if the seemingly infinite process of renewal in nature can mask the horror of loss and separation. A tree can lose its leaves and then grow new ones, they say, but when a child loses a parent the analogy ends.

If there is a cyclical kind of violence in seasonal change, this isn't really the violence that Howard is getting at. Every day, she says, we see destruction and pain in different parts of the planet, and the way this is channelled to us incessantly through digital media makes us lose our bearings. Are we in Syria or Iraq, Afghanistan or Pakistan? The sheer volume and omnipresence of these images generates an immunity, so that we no longer attend to the specificity of an act of violence or even know where it is taking place.

And yet Howard eschews any direct representation of military conflict. Why don't we see bombed out buildings, dead bodies or bomb blasts? The answer to this question echoes exactly her perception of our progressive numbing to global tragedies, our loss of contact with what is happening around us. Just as we fail to see what is before our eyes on our TVs, phones and tablets, so her paintings mimic this failure. She stages both our failure to see and the very mechanism that signals the inscription of a trauma.

What kind of mechanism is this? In another of her early works, Howard painted a scene of three prostitutes in a room with a billowing curtain. The women indexed a fascination with the figures of Schiele and Klimt, with vivid reds for lips and nipples, but why the mundane and monochrome curtain? To offset the figures, perhaps, or to express symbolically some underlying emotion. But more fundamentally, Howard observes, it was just a curtain, a contingent detail that had no special meaning in itself.

When people have experienced traumatic events, it is precisely this random and ineffable dimension that comes back again and again: the colour of a carpet, the pattern on a wallpaper, the grain of a wood. They are often unable to remember what happened to them in that moment. but the colour or the pattern or the grain will return in their dreams or thoughts with a terrifying clarity- as if the scene itself, unable to be registered psychically is inscribed purely through this nonsensical detail. This gives the structure of Howard's new works.

As we scan the pristine surface of these paintings, we see again and agel the repeated figures of a wallpaper pattern. or the inbrint of a shadow, or alighter space to mark where a figure had once been, like the traces left by some presence in the past. The eye is encouraged, as Howard says, "to settle and rest, settle and rest", moving around incessantly as it is led back to these points where we imagine that something had once been. These are the "invisible marks" that Howard is so drawn to, signs of both our failure to see the whole picture' and of the process through which a detail comes to stand for what cannot be imagined or thought through. How strange that these paintings, which seem so light and ethereal upon first view, constitute in fact an art of trauma.

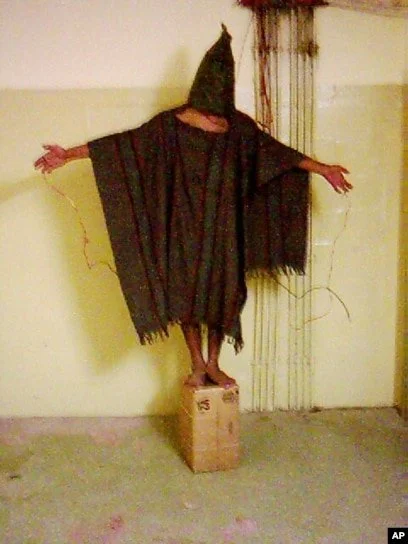

Her 2005-8 series Repetition is Truth - Via Dolorosa, which ran through the Stations of the Cross, followed this same logic. When Howard saw the now famous image of a prisoner being wired for electrocution at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, she was struck by the way this echoed the Christian imagery of the Passion. He was standing with arms outstretched, elevated from the ground by a box, in the process of being tortured: all the elements, indeed, of the crucifixion of Christ. There was even the presence of a witness in some of the images.

Photograph of an Iraqi prisoner in Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq 2004

Yet what intrigued her more than anything else here was the box, this random, contingent, and meaningless detail of the scene. "Why was it there?" she would ask, "Who had gone to get it? Had they chosen this one box rather than any other?" As these questions multiplied, she knew that the box would have to function as a focal point in the series of paintings. Like the more recent works, it is this detail that draws onto itself all the intensity and violence of the scene, like the wallpaper figures or seemingly random marks that haunt the new paintings.

Howard compares this to looking at crime scene photography. After spending considerable time analysing different images, the impact of the dead body itself seemed muted. What fascinated her was the anodyne wallpaper in the rooms in which these terrible crimes had taken place, just as in a Sickert painting our attention may be drawn less to the pain of the figures in the scene than to the drab, everyday backgrounds, the details of furniture and fabric. They act as a conduit for the rawness and unthinkable violence of a scene while at the same time reminding us of the fact that we are not really seeing it, that the saturation of images deprives them of their potential force. They have become as everyday as the wallpaper.

Eva 2004, Household gloss on canvas, 167.6 x 121.9 cm

Howard's technique here replicates this process. She had wanted to paint using pattern motifs for many years, and one day, as she was driving near her home, she saw some curtain roll for sale at the roadside. She would use this as a stencil on her canvas, emphasising the iterative designs in order to arrive at their point of disruption. Pattern itself suggests the home, Howard explains, together with a certain sense of security, yet her way of working over the resulting paint renders it imperfect, asymmetrical, "like the glitch that appears when you press the front of a calculator". Irregularities, distortions and dissolves punctuate the paintings' surface, taking us from the homely to another space.

It is surely not coincidental that the focus on the contingent domestic detail comes in Howard's work after the powerful series of paintings in which she does in fact represent directly the agony of the dying body. In her suicide drawings and paintings from 2006, we are not spared the horror of bodily pain, as she moves to an alternative way of approaching this via background rather than figure. Like the settings of these human deaths, she takes what we don’t see - the backgrounds we pay so little attention to - and transforms them into a lens through we are drawn to something beyond them.

Once again, her compositional technique in these earlier images reflects the subject matter itself. A scene had been described to her in which a man had hung himself while crouching on the floor, a reversal of the more usual way in which this type of suicide occurs. He must have strained against gravity, she thought, pulling his head downwards, showing how the body’s relation to gravity can be matter of life and death. With her gloss, Howard would allow the pigment and the varnish to separate in the can, apply the pigment to the canvas, leave the paint till almost dry, before pouring clear varnish on top to produce the effects of gravitational pull on the images.

This focus on the dying moments of a body echoes once more the motif of the Passion. Just as the image of the crucifixion would imprint itself on centuries of Christian art, so Howard's appropriation of it gives it this central place of a coalescence of beauty and suffering. In this sense - and only in this sense - Howard's art is religious, in that it presents an image which points to a realm beyond itself. This had been the classical Christian interpretation of the crucifixion, an image to cancel out all other images and which would lead the viewer to another; hidden reality.

And yet if so much Christian art conjugated this single image to condense all the sufferings of the world, Howard is approaching this problem from a slightly different angle. For her, the starting point is precisely the fact that we don't differentiate, we don't distinguish the violence all around us and render it particular. The "banality of violence" that she speaks of is everywhere, and the acts of destruction she evokes cannot be superimposed one on the other. That's why we encounter not direct representations of human brutality but leftovers, traces, backgrounds and shadows.

Just as classical Passion scenes would often accentuate the quality of their own painted surface as painted surface to amplify their artificiality, so Howard's Paintings of Violence point to their own screen-like quality, in order to trouble it. And, as she says, "what lies beyond them is a point of fracture, of bodily dissolution". Her technique with these paintings both mirrors and inverts the Christian sequence. A fluorescent pink background is overlaid with crimson oil paint, to generate a layering in which we are carried from "dry caked blood to the raw flesh below". We follow the Christian motif of the screen which takes us to a space beyond itself, while at the same time this space is bodily rather than abstract. The paintings, Howard says "are like wounds on the wall".

The violence that Howard so often describes is curious, as, in contrast to many other painters, we hardly ever see her brushstroke. We never feel the visceral torsion of a Ryman or the vital or mortifying rage of an Auerbach or a Freud. It is as if there has been no direct contact with the canvas. When Howard says that "I want to be removed from my work, to tiptoe away from it", we feel this withdrawal as we search for the mark of the painter's brush. And yet in so much of her earlier work, rather than brushstroke we find blocks of colour, reminiscent in many ways of the American abstract painters who had, at one time, inspired her.

Swathes of colour are indeed everywhere, yet how strange then to find the artist claiming that "I almost see colour as a weakness" and that "the challenge is to paint without colour". This brings us back to the question of violence. Howard explains, what interests her is not the block of colour but the edge that separates one from the other. She is not painting colour, but edges, barriers, limit points and this edge is a bodily one. She compares it to the moment when one hand brushes another in passing a stranger, a small act, a second of contact, yet one which may or may not herald something else.

Howard is different here once again from so many of the American abstract painters, for whom the edge that separates two blocks of colour is precisely that: a separation. Yet Howard's edges are not forms of separation but, as her invocation of the hand makes clear, forms of contact. It would be illuminating here to compare Howard's edges with those of other British artists - Caulfield or Hume for example - and to reflect on what function the edge has for them: is it to keep two bodies apart or to bring them together, is it to limit an expanse of paint or to deepen it, or, to borrow a question from the King Kong movies, is the barrier there to keep something out or, on the contrary, to keep something in?

It is tempting here to return to the boxing image, and the idea of the violence that one body can exert on another. Howard takes this violence, this point of contact, and transforms it into a question of edges, of the line where one space touches another. She has excised the violence from bodily contact at one level, yet retained it at another, and we could link this motif to her own experience of the body. Some of the artist's earliest memories are of the anticipation of physical violence, and she also came to fear the potential violence that she recognised inside herself. She describes how she would wait terrified for the punishment to arrive, and her world at this time was predicated on fear, with the pervasive thought that "a force would suddenly crush me".

Howard's art absorbs and develops many of these themes. The physical violence would stop when, one day, she protested. She said enough is enough. The rule of crime followed by punishment had to be broken. And in her work it is exactly this logic that prevails. Art might not seem to have any rules, she observes, but in each phase of her work she fixes on some set of rules, in order to reach the point where she can break them. "It's about breaking my own rules", creating systems to then overturn them. "My work", she says "is about disputing a rule".

We see this in what would be the painting that "changed everything" for her. After a time experimenting with perspective features and figures at Goldsmiths, she painted a solid white background with four clear black lines across it, like the musical stave. She titled it with the mnemonic used by children to remember the notes on the lines of the treble clef: 'Every good boy deserves favour.’ Yet the musical resonance was imperfect: she was careful to omit the fifth line that would have generated the appropriate symmetry. The painting was no longer a painting “about” something, Howard says, but involved “a leap of faith” perhaps the faith in abstraction as a pathway to elaborate the question of the body and the point of contact with it.

Contact moved from the impact of the bodily blow itself to the contact between the fields of paint, and in this work she also painted the breaking of a rule. in leaving out the fifth line that was necessary for the musical law. The title played cheekily on this act of defiance: if she had once inhabited a world that revolved around the weight of sin and guilt in which she was “the bad child”, there was now a ‘good boy’ who deserved favour, yet a good boy whose representation consisted in nothing less than breaking a rule.

Art had allowed Howard to transform her experience. It let her 'remove things from the immediate", to "knock them back a bit". A bodily blow, the point where one body touches another, could become the point where one block of paint touches another, an edge, just like the horizon line that she would scrutinise every day as a child, and, as she notes with a smile, like the name of the village that she lives in today: Edge. A line could function as a horizon, perhaps, in both a literal and a metaphorical sense here, as a geometry and as a way out, an access to another space. If it was indeed through this elaboration of an edge that Howard could use art to change her world, to distance "the immediate", it is nonetheless this very abstraction that she continually challenges in her work. Through the encounter with her paintings, she wants us to question the "banality of violence" and to bring things back, precisely, to the immediate. She wants us to think about what lies beyond the wallpaper, beyond the surface, beyond the fissures that so often open up in an otherwise unbroken layering of paint. If she has always challenged her own rules, her aim here is no exception.

This is what gives Howard's art its movement, its beat and its conflict. It is as if she uses her solution to contest her solution, as if the sublimation that she created had to be undone time and time again. The edge takes us away from the force of a bodily impact but the painting still brings it back, just in different ways. It is perhaps no accident here that sculpture has, in the last few years, begun to shadow her painting, from the stack of red-stained towels in the Paintings of Violence to the flower memorials that feature in her current show. As an artist of "what was there before", of traces, of marks that have been left, this dimension can never be forgotten or emptied out. Like the eddies, stains and halos in the new paintings, they remind us of what was once present.

Artworks:

Study 2005

Household gloss & acrylic on board

61 x 61 cm

Repetition is Truth

- Via Dolorosa 2005-2008

Household gloss on canvas

289.6 x 190.5 cm

Painting of Violence (3.10)

2010

Acrylic & household gloss on canvas

182.9 x 182.9 cm

Paintings of Violence (Why I am Not a mere Christian)

Oil & acrylic on canvas, wood 7 x towels & pigment